If you want to be as cool and go as fast as Tad Elliott, you need to first buy a bad-ass El Camino and then next get a Suunto Ambit 3 heart rate monitor and Firstbeat HRV software.

This review of the Firstbeat heartbeat analysis system originally appeared on SlowTwitch.com, a publication targeted for triathletes (see Part I, II and III). This version has been added to and updated specifically for nordic skiers.

He says they’ve already got one…

Monitoring training load is the Holy Grail of endurance athletics. Any good coach will always be looking at how to optimize training load, and essentially every competitive athlete from the first time they toe the line will wonder how to best balance intensity, volume and recovery. Throw in the added and significant stressors of work, school and social obligations and this already complicated equation becomes even more involved.

As the world becomes increasingly digital and the science more precise, the last few years have brought a number of different technologies to the plate that look to better quantify training and recovery. Heart rate monitors have been a staple of endurance training for over three decades. With the increased prevalence of smart phones and their ever increasing functionality, the ability to collect data has never been greater. Even more recently, a speciality market of “fitness trackers” has emerged with devices 100 percent dedicated to tracking movement, heart rates and a variety of other metrics. Several of the big players like Apple have gone a step further (no pun intended) and incorporated these features into everyday wrist watches, so finding ways to clutter your hard drive and mind with biometric data is now easier than ever.

One area which is ironically much less clear however, is the overall effectiveness and utility of all of these devices. Your functional threshold power (FTP) on the bike is 407 watts? Great. Now what? I didn’t win bike races by having a better FTP than the other riders, I won races by getting to the finish line first. Same deal with heart rate. Now before all of you data geeks fire off an angry email that these metrics are tools to help better guide athletes to the podium, I agree with you, but what if there was something that allowed you to quantify both work and recovery? Something that provided insight into not just the physiological stresses of training but also in activities of daily living (ADL). There is. And it is called Firstbeat.

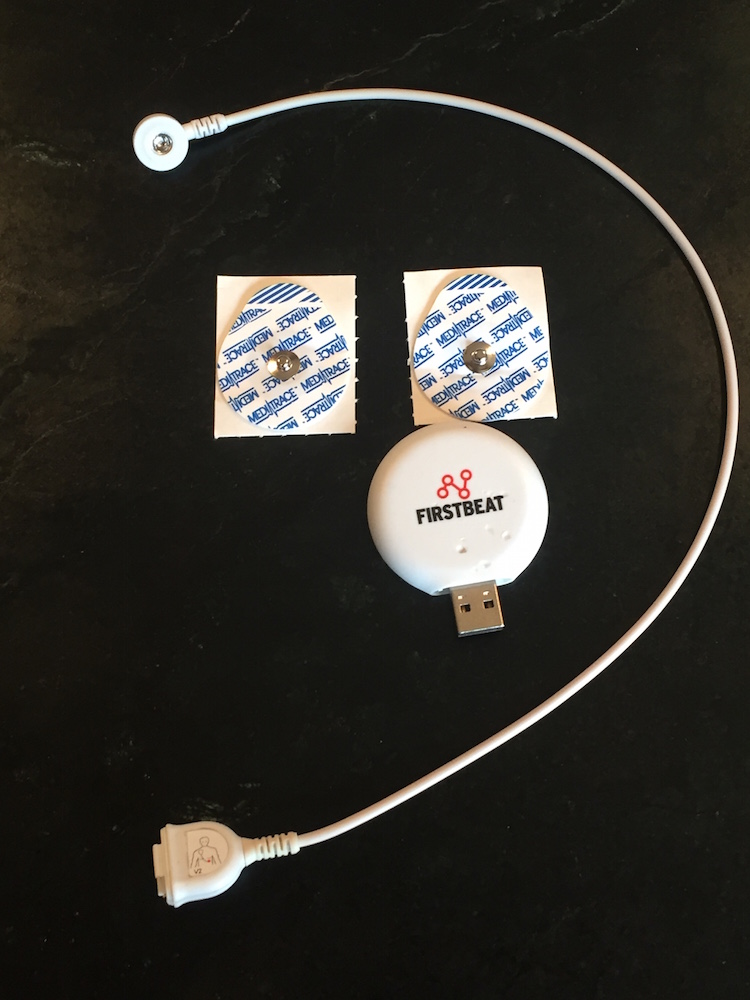

The Firstbeat system can be used with a traditional heart rate monitor chest strap or specially dedicated chest sensors as pictured.

HRV

The Firstbeat system (FB) is a member of a class of devices that monitor heart rate variability (HRV). In simple terms, HRV, as the name implies, is the difference in the intervals between heart beats. Different devices approach this situation differently, but in essence, Firstbeat uses a mathematical algorithm to compare heart rate, interval regularity, maximum heart rate and VO2 to calculate a few different output and recovery metrics.

How it works

One sport early to adopt HRV monitoring is nordic skiing. Three-time Olympian and former U.S, Ski Team coach Jim Galanes, offered his history with the device.

“Tina Hoffman, who was a coach at University of Alaska, Anchorage, showed this to me about eight years ago, so I’ve been studying this system for quite a while,” Galanes, who co-owns Galanes Sports Systems and handles the distribution, sales and service for Firstbeat products, explained on the phone. “The more I used it, the more convinced I became that it is a very effective tool and by far the best one out there. I’ve become so convinced of its effectiveness that starting four years ago, I won’t coach anyone who won’t use it; it is that powerful. It is the single best way to making training decisions.”

Zach Caldwell, coach of several members of the U.S. Ski Team, has been working with the system for a few years and provided a more in-depth explanation of the underlying science. “Your heart rate is governed by your central nervous system (CNS) through two central pathways in your autonomic nervous system: your sympathetic nervous system and your parasympathetic nervous system” Caldwell said on the phone. “Your sympathetic nervous system is what governs your ‘Fight or flight’ response, in common parlance. This is a stress response. It elevates your heart rate and creates a signal that makes the beat to beat interval very regular.”

Caldwell continued, “The second component, your parasympathetic nervous system, which governs rest and relaxation. The influence of the parasympathetic nervous system is to lower and create less regularity between heart beats. By looking at an individual’s heart rate (HR) variability in comparison their own baseline, you can make a statement about the prevalence of a sympathetic response, which is an indication of stress. In short, by using the Firstbeat system we can see how your body is responding to stress. It is a fairly direct measurement. I am not a scientist or a doctor, so while I have reviewed some of the literature, I can’t speak to the experimental design, but my read of the science is that there is ample support for the efficacy of utilization of heart rate measurements of indications of CNS function. CNS pathways are integral for heart rate regulation, so this is very pertinent for sports. Their appears to be very good science and very good efficacy of that science toward athletics.”

Galanes agreed, “A great deal of research, thought and testing has gone into this system: is the result of life work of Heikki Rusko, one of the best sports science researchers in the world, so the system is very well grounded in science, as the research that went into validating the system spanned over 15 years. From this perspective, unlike a lot of systems that are out there, this has gone through rigors scientific validation, both for monitoring training and recovery.”

The key, according to Galanes, isn’t just what the Firstbeat system measures, but what it does with it.

“There are a lot of systems out there that collect data, whether it is a regular heart rate monitor, power meter, Strava, Fitbits, whatever, but there is very little analysis that goes on with that data. Using HRV and the Firstbeat software to look at training load and recovery has become the gold standard. Power and HR are certainly useful, but alone they are not good measures of the disturbance of homeostasis on the body and that’s what training and recovery are all about.” For those interested in a much more in-depth presentation of actual data fields and a more detailed explanation and description of the software, check out this webinar: https://www.firstbeat.com/en/webinars/training-load-recovery-monitoring-in-professional-xc-skiing/

Why Use It

“Coaches and athletes are all very concerned with stress and recovery,” said Caldwell. “Previously I don’t think we have done a very good job at looking at this holistically, so while we looked at rest, we didn’t look at enough factors. The ability to examine and even quantify the role of stress both independent and related to training load is very powerful. This is particularly important for self-coached athletes, for as athletes, we tend to be good at lying to ourselves. Athletes are delusional. We take a lot of information on board and we interpret it based on what we want the outcomes to be. I see it all of the time. I can tell if an athlete is tired and I think even that athlete knows it, but when you ask them, they say they’re fine, in particular at the elite level. I work with over-motivated athletes who want to be able to do more. This isn’t a tool to tell you to take it easy, rather it is a tool to help you make better choices.”

Erika Flora, head coach of the Alaska Pacific University (APU) elite team, agreed. “It can be a good tool if used correctly and in combination with other indicators, in particular feel — I am a big believer in teaching athletes ‘feel,’ ” he said during an in-person interview. “HRV is not an absolute indicator, but it is definitely useful, as sometimes motivation overrides good judgment.”

The 24-Hour Athlete

So often the motivation to try harder is bundled into the four hours of training each day and the other 20 hours in the day are ignored, or at least not optimized,” theorized Caldwell. “If your job has had you running around all day, it may actually be counter-productive to do the interval session you had scheduled. This system is a tremendous help in monitoring your overall stress and adaptation. Careful and correct interpretation of this data can create what I call ‘better 24-hour athletes’.”

Caldwell continued, “One of the major things we want from training is to see a positive response. It sounds so basic, but I see so many good athletes mess this up. We want training to make you stronger. You do a hard training session, we hope that this will make you better, that’s the goal. It’s easy to skip the part where we ask, ‘Is this really going to make me better? If so, when?’ This is a tool to help answer the question. I am unconvinced by things for which I don’t see evidence. I see lots of people doing lots of hard work, but I don’t always see benefits. Why? Training should work. As a coach, if an athlete is not getting better, I want to know why. Why are they not responding positively to training? If we’re counting totally on self-reporting, well, that doesn’t work very well. Most of the good athletes I know have a very good way of coloring their own training. You can beat them into the ground with tests, but that also has its limitations and is disruptive. What if you had a tool that could quantify all of these factors. What if you knew who had good sleep and recovery? This tool does all of that.”

How to use it

Essentially the Firstbeat system measures two primary factors: training load and recovery. The two are obviously related, but can also be uniquely independent. Training load is monitored through a combination of factors, in particular, Excess Post-exercise Oxygen Consumption (EPOC). Measuring EPOC offers several advantages over measuring power or heart rate alone.

“EPOC is very interesting in that it helps you understand the load that you feel when you’re training is cumulative, not instantaneous,” noted Caldwell. “The cool thing about EPOC is that it looks at accumulation of effort over time. The best athletes have a great sense of how to keep things ‘easy’ — their HR can drift up a bit, but they can feel the recovery. What I see in less accomplished athletes is that they religiously follow the HR monitor, so sessions designed to be easy oftentimes aren’t so. Typically amateurs overdo it on easy days and under train on hard days. Using EPOC to help monitor this is huge.”

“Granted, my case is somewhat unique,” Caldwell continued, “as I exclusively coach elite skiers, so EPOC scores are useful, but the recovery thing is even more useful for me. The recovery score is great because it utilizes HRV as a real-time score. The recovery score is an indication both of the level of recovery and the level of fitness. You can’t rest your way to a great recovery score any more than you can rest your way to a great performance. Your peak recovery scores come in relation to your peak training loads and your best management of the recovery process, so it’s not just rest – paradoxically it is also training load.”

Galanes followed up on this thought: “This system is based on understanding each individual’s unique physiology. To use this system optimally, you need to start out and do some testing programs on things like max HR and help determine max VO2. So you need to do a six-minute max test. This helps set a good benchmark for all of the data. This is key, as you need good data going into the system at the start. Once you have this, all you need to do is start training and understand the simple observations of EPOC. The information you get from the system gives you the tools to quantify the training load but also ask the questions about how to modify training to improve overall capacity and performance. The human body is always in flux: it is always adapting to load, so the body is not the same day in and day out and FB is one of the best systems to quantify these changes and better define these different states of readiness.”

Over-The-Hill Gang

One group Galanes believes benefits the most from HRV monitoring is masters athletes. “Recovery profiles for masters athletes are very, very different than young, elite athletes. As we age, there is a whole different training process that needs to occur. Ned Overend, Joe Friel and others are making some good observations on this. Since we all age differently, FB is one of the best possible tools to assess each individuals response in training and recovery. The real value at looking at EPOC is to help you understand if you’re getting the desired effect of your training. If you go too hard, you are compromising something later in the training process. It really helps clarify the focus and the implications of the training. It is the most incredible training tool that has come along in my training and coaching lifetime.”

Optimal Usage

As a frequent traveler to both Europe and high elevation (sleeping at 7,200 feet, training between 6,700-10,400 feet), being able to measure the “stress” and overall physiological impact of traveling to and training at these sites have proven to be incredibly valuable. Sure, any idiot knows that they’re tired when they get off the plane after a nine-hour flight, but what does this really mean in terms of training? Should you even train right off the plane or take a nap instead? If you do go, how long and hard should you go? Firstbeat can help answer all of those questions. And that’s just the tip of the iceberg.

Anyone who knows me knows that I lead a very unusual life. I spend more time on airplanes than many people do in bed. I have a large animal rescue and much to the amusement of my vet and farrier, I often ride my mountain bike to my farm to administer vaccines to the animals while wearing a full cycling kit (apparently this isn’t all that common). I also regularly work on three continents, ski home from work in the dark and a bunch of other stuff too strange to print, so I think most would agree that I am clearly an outlier on the curve in many ways and in many things. Now, having said that, while my stressors may be different from yours, my guess is that each and every reader out there has lots of other demands for their time outside of training and lots of factors that impede recovery, some unique to them, others not. Sure, most of these stressors most likely don’t involve giving vaccines to donkeys or having the entire U.S. Ski Team’s jump skis lost in Japan, but I have yet to meet the person who claims their job is easy, who gets all of the sleep that they’d like and who does not have any worries or responsibilities. So just how much is your stupid job, long commute or inability to attract a member of the opposite sex affecting your training? More than you might expect.

Sure, most of these stressors most likely don’t involve giving vaccines to donkeys or having the entire U.S. Ski Team’s jump skis lost in Japan, but I have yet to meet the person who claims their job is easy, who gets all of the sleep that they’d like and who does not have any worries or responsibilities.

“The thing that the most interesting about it is that it provides hard data on feedback that helps us modify our behaviors in ways that are otherwise difficult,” claimed Caldwell. “I first started using Firstbeat when I was traveling in Europe. I found that I was getting high EPOC scores on runs that I thought were easy. As soon as I recognized the stress from the long travel and adapted my training, I got better EPOC scores and felt an immediate fitness bounce. Don’t get me wrong, it took me years to learn this lesson and I had to learn it the hard way. Generally us old dudes go out and hammer. Most masters skiers train like they’re going to win World Cups. That’s just wrong. We’re exercising our fantasies, not reality. This system helps stop that and allows you to train smart. It can both slow you down and speed you up, which is an important mix. Generally our instincts don’t always line up with the true need of the situation and figuring out how to keep this in check is very, very important.”

U.S. Ski Team member Noah Hoffman with his Suunto Ambit heart rate monitor, compatible with Firstbeat technology.

One of the elite athletes that Caldwell coaches on the U.S. Ski Team is Noah Hoffman. Hoffman’s perspective is interesting in that he is exclusively focused on outcomes, not on any of the theory or science behind the system.

“I don’t really look at the numbers; I rely on Zach for that. All I know is that it helps me a great deal,” Hoffman said during an in-person interview. “I’ve been using the system for a while and I love it. It gives me piece of mind when I’m going into a big training block that I can handle the training load. I know I’m not going to drive myself to oblivion. It’s also very valuable if you start to feel rundown from travel or illness, as it gives you good feedback on just how much you should back off or push through.”

Another elite skier to use the system is Sophie Caldwell, winner of a World Cup this year. “I’ve only been using it for about a year, but I love it,” she said on the phone. “When I see my recovery trending downward, I can catch it early, which is so key. It’s also been very interesting to see which workouts take more out of me. I’ve noticed things like if I’m in Level 1, I can go forever, but as soon as I start going into Level 2, there is a much bigger cost there. I know this is very different for different people, so this allows both the athletes and the coaches to see that different workouts affect different people in different ways. Liz Stephen [U.S. Ski Team teammate) and I are both coached my Matt [Whitcomb] and we’re amazed when we compare data on how different workouts effect us. I find this fascinating and it clearly shows how important individualized monitoring is for athletes. If Liz and I were attempting to follow the same program, it wouldn’t work well for either of us. So thanks to the data and insight we’ve gotten from the system, we’ve all learned a lot about ourselves and training.”

Without a doubt the most ringing endorsement came from Tad Elliott, who had a history of illness and overtraining. “Firstbeat saved my career. I was so sick and struggling so much with how to carefully and gradually return to full activity, I never could have made the comeback that I did without Firstbeat. It is that important to me. Now, my case may be a bit extreme, but it is most certainly very useful for all endurance athletes, in particular busy ones.”

Weaknesses

Is this system perfect? Of course not. Firstly, to achieve nighttime recovery data, here’s a shocker, you have to wear something when you sleep. Firstbeat gives you two options: your traditional HR monitor chest strap or specially dedicated chest sensors.

The HR monitor chest strap is easier, cheaper and I suppose looks less weird (though a word to the wise: prepare yourself for lots of comments/questions from your significant other). The disadvantage is that this setup is more prone to error. The chest sensor option is very, very accurate, but not only do you have to buy electrode patches (cheap, but a PITA to remember to bring on trips and re-order) you also look like you are undergoing screening for the Mercury space program every night as you prepare for bed. The system provides uber-accurate measurements, but sadly I found it to also be a bit wonky. If you do not upload the data every few days, you experience the dreaded “system crash and freeze” therein losing all of your data. This is not an issue if you stay on top of your uploads, but it seems as though this should work better for a system of its price. Sleeping with either contraption is a bit of an adjustment, but thankfully FBD is a good sleeper and after a few nights I don’t even notice either option. Your mileage may vary.

Japan’s Akito Watabe, a 2014 Olympic silver medalist, showing off his Suunto Ambit heart rate monitor.

The system requirements claim that it can work with several different heart rate monitors, but everyone I’ve spoken to uses a Suunto Ambit 2 or 3, myself included. I found the Suunto to be superior to the Garmin even as a stand-alone HR monitor, so using it for FB was an easy transition. And I’m not alone — look on the wrists of many a World Cup skier and you’ll see a Suunto, so I don’t view this as a negative, but knowing that you may need to also buy a new watch is an important consideration for budget and ROI. Then there’s the issue of the software not running on Mac. This can easily be overcome by installing an emulator, but again, it seems like software of this price should be Mac compatible.

On a more macro level, “power user” (see what I did there?) Zach Caldwell offered a few more criticisms, “Overall the software could be a bit more user friendly. There is a lot going on, which is a good thing, but this means that it can take some time to understand how to correctly interpret the data. Perhaps more importantly, it is a speedometer. It tells you how fast you’re going. It does not tell you how fast you should be going. This is not a weakness, but rather a common misperception of the utility of the device. It is a fantastic device, but all users and potential users need to be aware of what is actual does and does not do.”

Galanes seconded this observation, “People make the mistake of buying the software, installing it, going for a run, then looking for something magical. It doesn’t work that way. You need to establish a baseline for recovery, do some VO2 tests and begin to look for trends. It takes a few weeks before the data will start to be meaningful and you need to understand how to properly interpret it, but once you have all of that down, it’s the best thing out there by a long shot. If you can work with a qualified coach who has experience with the system, that’s the best of both worlds.”

“People make the mistake of buying the software, installing it, going for a run, then looking for something magical. It doesn’t work that way. You need to establish a baseline for recovery, do some VO2 tests and begin to look for trends…” — Jim Galanes, Olympian, former U.S. Ski Team coach and current Firstbeat rep, on Firstbeat system

Flora also believes that metrics such as heart rate, lactate, etc., need to taken in context and used as a part of the “big picture”. “HRV can help athletes see trends and match up with what they’re feeling, which is very important, but using it as a main driver can be complicated,” he said. “I am a big believer in athletes learning how to understand what’s happening with them.”

Biggest Takeaways

“I’ve been around sport for a long time,” said Caldwell, “first as an athlete and then as a coach and one of the biggest things that I see while advising my athletes is just how hard it is to coach yourself. I include myself in this, too: my personal instincts for training are terrible. Every basic instinct I have is to run myself into the ground. I always thought I just wasn’t tough enough, but in reality the problem was that I was way too impatient and way too stupid. I wanted to go faster right away and I didn’t want to listen to my body. I know this is not just me either, so being able to quantify some of these issues helps me have a good discussion with athletes in a very non-threatening way, which is important.”

“One of the biggest things that I’ve learned is just how right coaches are,” Hoffman said. “As athletes we always hear about the importance of rest and recovery, but we you can look at the data right on the screen about how your behavior impacted your ability to train, that is much more powerful than anything a coach can say.”

Fellow U.S. Ski Team member Sophie Caldwell agreed, “I’ve become a lot more aware of my recovery and the impact that different workouts has on recovery. It makes me think a lot more about how important recovery is for success. It’s forced me to pay more attention to all of the other parts in my day and that’s a good thing, a very good thing. I’ve been using it for almost a year, and while I’m not at the point where I rely on it 100 percent, it is very helpful to see my trends. Sometimes it shows that I’m getting into a bit of a hole and this helps me stay in front of it. I also use it to ramp things up if it looks like I can handle more load. I can probably do a pretty good job guessing, but I certainly would have missed it a few times and it is in those instances that it is particularly helpful. My overall experience is very positive.”

Hoffman continued, “One of the first things that I did when I started using the system was I collected data for 24 hours/day for 6 weeks. What we learned with this is that my activity through the day correlated much more highly than I believe earlier to my nighttime recovery scores. Some of the coaches had told me that they thought I was being too active in between training sessions and that’s exactly what we found. It was also surprising the types of things that disrupted recovery. I’m a competitive guy and it turns out that even board games elevate my stress levels enough to impede recovery. I never would have guessed this. It’s also important to note that while we have prioritized recovery in our use of the system, I definitely do use it for training and racing, in particular for things like pacing. It helps you verify what you think you already know in terms of feel. I look at it as a great safety net.”

Applicability for Age-Groupers

So is this just a tool for the over-80 VO2 crowd with Olympic aspirations? Hardly. In fact, given the complexity of training for any race while working full time, this system is probably even more applicable to age-group athletes. “It’s probably more important that people who aren’t full-time athletes use this system,” noted Hoffman. “It’s WAY harder to balance your training load that manages your energy appropriately, as non-professional skiers have so many other distractions. I can at least try to devote most of my energy to training, so it’s easier to recover and not overdo it, but for people who have lots going on, it would be incredibly valuable. It is an important guide to help you train effectively with everything else that you have to do.”

Zach Caldwell agreed: “If you use a system like Firstbeat to measure stress load external to exercise output, you’re nailing things down from both sides. Neurological state and physiological cost and that’s a great thing. Human performances lives in the gap between input and output. If you’re only quantifying one or the other, you’re opening yourself up for surprises on race day, I don’t care what sport you’re in.”

Parting shots

In this day and age of the “shallow reader,” this article was long, perhaps too long for the taste of many, but there’s a lot going on here and I felt it was important to accurately describe the power and limitations of this very exciting technology from multiple perspectives. How you proceed from here is up to you, but to help perhaps guide some of your next steps, I asked some of the people the most familiar with the system for their advice to those considering taking the plunge.

“Jump in with patience,” advised Zach Caldwell. “Definitely do it, but go in with realistic expectations. The system won’t pay dividends in the first week, but if you are patient for three months, you absolutely will not be disappointed. But you need to be committed: three months of wearing this thing to bed. Training with it every day. Doing baseline and follow-up testing. Learning how to interpret the results. But if you are consistent and patient, you will learn a lot. It is an incredibly valuable tool when used correctly.”

Galanes went one step further, “Balancing endurance and intensity training is not easy and finding that line without the insight that the system provides in very, very difficult. FB gives you access to much better data and a much bigger picture. It is going to change your paradigm on what is optimal training and it is going to change how you view endurance training, all in a very positive way, but you need to be sure you are using the system correctly. If you do, you will feel better and you will perform better.”

Elliott added, “If you’re juggling work, family, illness or any other stressor, I strongly encourage everyone to use it. I never could have made it back to the top level with the data I got from the system and I know it will help most, if not all athletes.”

“I’ve had a very positive experiences with it,” said Sophie Caldwell, “so I absolutely advise people to use it, but start out cautiously. Track your training and sleep, but don’t rely 100 percent on this system. You need a baseline, but the more time you spend with it, the more you learn to correlate how you feel with what the data is showing, which makes you even more comfortable with it and able to count it on even more. It’s not the only tool that I use, but I sure am glad that I have it.”

Hoffman summarized the whole process nicely and offered solid advice, “Take it slow at first. Firstbeat tells you a lot, so it can be a bit overwhelming. Take your time, learn what the numbers mean or find someone who does and be patient. It takes a while to understand how this is all relevant to you, so don’t get overwhelmed by it. Stick with it, though, and you’ll be glad that you did. You will learn a lot and you’ll be a better, happier athlete.”

For more information on Firstbeat technologies and pricing information, visit Firstbeat.com.