Colette Bourgonje racing at her 10th Paralympics in March, the 2014 Winter Games in Sochi, Russia. (Photo: Cross Country Canada)

Twenty-two years ago, Colette Bourgonje was a grade-school teacher with a ticket to the Albertville Paralympics in France. A Saskatchewan native, she had learned how to nordic sit ski a year earlier — all while teaching physical education in Saskatoon.

But the school wasn’t about to let her take off to compete at her first Paralympics. At the time, Bourgonje was paying her own way to do so, and since landing a temporary teaching contract in 1989, she was trying to secure more job stability.

Yet passing up the Paralympics wasn’t an option, she told herself. Bourgonje quit her job and resolved to find another one when she returned.

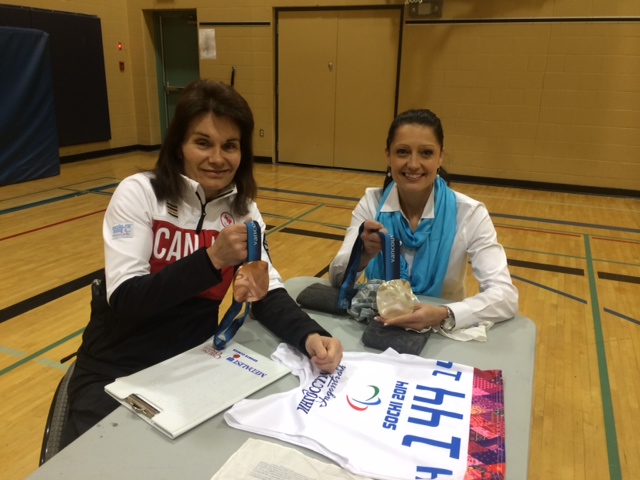

Ten-time Paralympian Colette Bourgonje (l) with Melanie Florizione, vice principal of a school in Regina, Saskatchewan, during an appearance after the Sochi Paralympics. (Courtesy photo)

A national-level cross-country runner as a teenager, Bourgonje was in a car accident her senior year, leaving her paralyzed from the waist down. Four years later in 1984, she took up wheelchair racing and became the first to graduate the University of Saskatchewan’s physical-education department in a wheelchair.

With the competitive bug back in her system, she tried sit skiing for the first time in 1991 and immediately fell in love. More similar to cross-country running than wheelchair racing, she began to work at improving in that sport as well.

After competing in Albertville in the winter of ’92, Bourgonje qualified for the Barcelona Olympics that summer. There, she won two bronze medals in wheelchair racing, and went on to claim two more bronze medals at the 1996 Atlanta Summer Games. She also raced at the 2000 Summer Olympics.

Not one to take a breather, Bourgonje became the only athlete in the world to compete in all seven Paralympic Winter Games from 1992 to 2014. She tallied six Winter Paralympic medals — three silver and three bronze — between the 1998, 2006 and 2010 Games, and went down in history as the first Canadian to win a Paralympic medal at home in Vancouver (she earned silver in the 10 k sit ski).

On the phone from her home in Prince Albert, Saskatchewan’s third largest city along the North Saskatchewan River, Bourgonje reflected on some of her career highlights in the last 24 years. At 52, she announced her retirement from the Canadian Para-Nordic Team late last month.

“Carrying the flags out in Nagano and Torino, carrying the Canadian flag out was absolutely fantastic,” she said of her flag-bearing honors. “Getting the first medal in Canada was an amazing experience. Being on the podium in that 10 k was just like, whoa. I was so happy.”

At Vancouver’s closing ceremony in 2010, she received the Whang Youn Dai Achievement Award, given to an individual at each Paralympics who has shown to conquer adversities through sporting excellence.

In her third nomination for Saskatchewan’s Female Athlete of the Year award, she won it in 2010. She remembered writing the acceptance speech, which she never expected to deliver, before a friend attended the awards ceremony for her in Saskatoon.

“I just whipped it off in five minutes really thinking I would never get that award,” she recalled. “We were in Russia and I think the other thing that happened that same week … I finally got a [World Cup] medal in Russia that was the only gold I ever won. I was just like, I cant believe this is happening! That’s why I would’ve been satisfied to say this was a great career.”

After finding success in Russia, Bourgonje decided to commit to another season through 2011 World Championships in Russia. There, she racked up another gold medal to add to her growing list, which included two overall International Paralympic Committee (IPC) World Cup victories in 1998 and 2005.

“After 2010, I did say that was going to be my last Paralympics,” she recalled.

Around that time, she asked one of her coaches, Peter Eriksson, the Athletics Canada Olympic and Paralympic head coach, how you know when you’re ready to be done. “He said you’ll know,” Bourgonje said. “And I did.”

Colette Bourgonje competes in the 5 k sitting at the 2014 Paralympic Winter Games in Sochi, Russia. (Photo: Matthew Murnaghan/Canadian Paralympic Committee)

The courses in Sochi simply weren’t for her. “It’s a great course for double amputees,” she said, with massive climbs and descents, not the kind of flowing course she favored. She had raced well at the December World Cup in Canmore, Alberta, placing fourth and fifth, but suffered from low iron and vitamin B12 levels in Sochi.

“I knew I did everything I could to be physically ready to race,” she said.

But she was tired. In three races, Bourgonje placed 13th twice (5 k and 12 k) and 16th in the sprint.

“It’s all good; it was fun,” she added.

Perhaps one of her greatest sports successes was Brittany Hudak, Bourgonje explained. Two years ago, she met Hudak, now 20, working at a local Canadian Tire in Prince Albert and persuaded her to try nordic skiing. Not exactly sure how to coach an arm amputee at the time, Bourgonje quickly became her mentor.

This past season, Hudak made her World Cup debut and qualified for the Sochi Paralympics.

“This year traveling and training with Brittany was great — it was great to see a different kind of success,” Bourgonje said. “She’s just having the time of her life.”

Without Bourgonje on the team this coming season, she said three men remain on Canada’s Para-Nordic World Cup squad and Hudak is the lone development-team member.

“She has a lot of people willing to help her,” Bourgonje explained. “I’ve been her mentor and the person she’ll come to asking questions, but she definitely has it all together and will get what she needs … I would like to see her racing in Korea [in 2018]. That would be pretty awesome.”

One of Bourgonje’s early coaches (along with Para-Nordic Head Coach Robin McKeever), Bruce Craven will continue to work with Hudak on her training plans.

“[Craven] has been providing me with programs since July of last year and still continues to write them but we are in the process of trying to get me on a yearly training plan which is different from what I did last year,” Hudak wrote in an email.

“Colette has had a huge impact on me in the sense that she was first an inspiration and a role model for me. Then she became a mentor for me which really helped me become a better skier in a short period of time.

Brittany Hudak competes in the 5 k standing at the 2014 Paralympic Winter Games in Sochi, Russia. (Photo: Matthew Murnaghan/Canadian Paralympic Committee)

“Since I was new to the sport I didn’t know who I could contact to learn more about getting started in the sport so Colette helped me out a lot with the resources that were available to me and informed me of what steps I needed to take in order to get to a high performance level of sport,” she added. “Colette was also willing to chat with me at any time if I ever had questions and wanted some advice so I think she was very good with being a friend and a mentor.”

As for what Bourgonje’s up to now, she recently returned from an Olympic/Paralympic tour at schools around the province and will continue to do similar speaking appearances throughout the summer.

“The Paralympics have not really been in the forefront — every speaking opportunity I get, I say it’s a parallel event to the Olympics…” she said. “It’s picking up, but it’s not yet at an equal … [or] seen as a parallel movement yet.

“When you medal at the Paralympics, you don’t come home to $ 20,000 dollars for medaling,” she added. “It’s a great movement, but it’s not well known.”

Between traveling around the Canada to deliver her message, Bourgonje also wants to return to teaching. While she’s taught everything from phys ed to health, math, and science, it’s the energy of the students she’s missed. Substitute teaching could be a good remedy for that, she said.

During her full-time racing days, Bourgonje taught part time until 2008, largely paying out of pocket to compete until 2005, when Team Visa started sponsoring her. She met Canada’s carding (government-funding) criteria for wheelchair racing at the Atlanta marathon in 1996, then received assistance from Cross Country Canada for nordic in 1998 leading up to the Nagano Olympics.

“You can be carded in one sport and they give you [$ ]1,500 a month at that time (that was the highest funding at the time),” she explained in an email. “Carding has now increased to [$ ]1,800 a month to live and train on.”

Eighteen months before the 2010 Olympics, she quit her Saskatoon elementary school job and moved to Canmore for what she thought was one final push.

“It was very stressful. I’d put everything on the line,” she told The Star Phoenix.

After the ’92 Winter and Summer Paralympics, she landed a job in Saskatoon’s recreation department. In 1994, the Burnsville school district hired her.

“I do feel that teaching part-time kept me grounded and very appreciative of what I received,” she told FasterSkier. “You know what they say whatever doesn’t kill you makes you stronger. I also loved my job and was only stressed out when I had to apply for leaves in the winter to go to compete.”

Colette Bourgonje doing some mountain-board work during a Canadian Para-Nordic Team training camp in Arizona two years ago. (Photo: Robin McKeever)

In the last couple months Bourgonje has backed off full-time training to enjoy more recreational outings — like kayaking — and said she’s looking forward to skiing in the Nisbet Provincial Forest with her partner George, who grooms the trails right out of their backyard.

“I’m really wanting to enjoy and not feel stiff and tired — no more four-hour skiing for me,” she said. “A couple hours to enjoy wherever we are absolutely [doing] … or skiing with kids.”

Last year, she met an 8-year-old boy named Tyrese, who’s missing part of his arm, while shopping for batteries for her heart-rate monitor.

“He was getting into a little red car they have set up at the mall, I asked him if he liked skiing he said he did so I asked him where his parents were,” Bourgonje recalled.

She talked to his mother, gave her a card with her contact info and asked where Tyrese went to school — just in case they forgot to get back to her. After a training camp last October, Bourgonje went to his school to see if he was still interested.

“We set him up with skis/poles but he had no boots. While we were in Canmore, the school bought boots for him,” she explained.

Later, Bourgonje brought him to ski on the trails near her house. When she returned from Russia in March, she took Tyrese and a sit-skier out on less-than-ideal conditions. But they stuck with it.

“Right now we have another 12 year old with no arms, Tyrese, Kristen, a girl in the hospital, a six year old, and a girl I am [bringing] a racing chair to today…” she wrote on Friday. “So setting up something for all of them to be active seems to be the way to go.

“[Tyrese is] a reason to stay in shape and go skiing with him and see the smile on his face,” she said. “Exercise is a lifestyle and you can’t just stop.”